Cleveland Whitehead Jr. beams with excitement when he discusses life on the Flint River Farms Resettlement Project. The 78-year-old grew up in Macon County. He witnessed historical changes that helped African Americans become self-sufficient.

“Growing up on the Flint River Resettlement Project we thought we were big shots,” Whitehead fondly recalls. With the arrival of the resettlement project, the standard of living changed dramatically. According to Whitehead, in 1938 the average farmer's worth was $73, and by 1943 it improved to $300.

The Flint River Resettlement Project was one of many emerging programs during “The New Deal” era of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration. Developed in 1937 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), its main purpose was to give African American farmers, most of whom were sharecroppers on plantations, the ability to own farmland. This would allow them to enhance their farming skills and improve their way of life.

To this day, Whitehead commutes two to three times a month from Atlanta to maintain a home on the original 178 acres purchased by his parents, Cleveland and Pennie. During his visits, he tends to his timber crop on his share of the land and engages in bush hogging. Bush hogging is the removal of brush from the ground with a tractor and a mowing tool.

Beginning in 1935, federal programs such as the Resettlement Administration, succeeded by the Farm Security Administration, developed plans to lift farmers, sharecroppers and tenant farmers to landowner status. To help battle poverty in rural areas, the agency purchased more than 1.8 million acres at 200 locations across the U.S. In the South, 13 resettlement communities, comprised of 92,000 acres, were reserved for 1,150 African American farmers and families. One of those communities was Flint River Farms.

The community was originally scheduled to be in Peach County in Fort Valley. Plans were approved in June of 1936 for a settlement of 150 farms, a health center and a school. However, after strong opposition from residents who filed petitions against the project, it was decided to move it to Macon County.

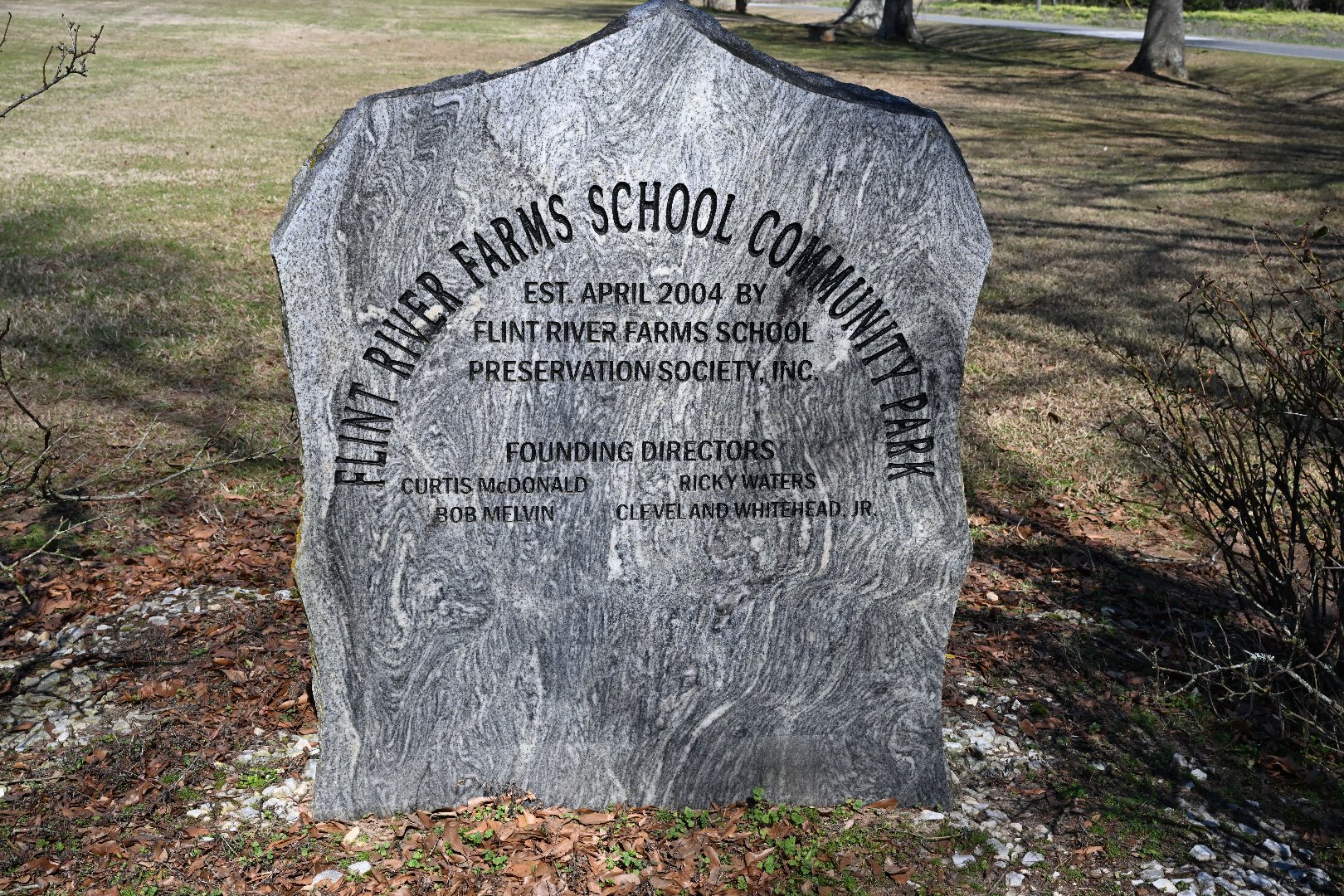

Whitehead said the chapel and the school were located at the center of the settlement where a monument now stands.

“The chapel and school served as sites where they held community meetings. Doctors and nurses came there to provide care, and student teachers from Fort Valley State University came there to train,” the retired law enforcement veteran said.

Additionally, some of the crops grown on the settlement included cotton, corn, peanuts and various fruit trees. Whitehead said if a farmer needed a piece of equipment, they could borrow it from their neighbor.

From 1937 through World War II, the settlement thrived. After that, it declined slowly. Once the Flint River school closed in 1965, the settlement shut down.

In 2004, Whitehead, along with fellow Macon County residents Bob Melvin and Curtis McDonald, decided to form a committee to help preserve the history of the settlement. With the help of several individuals, including retired FVSU Macon County Extension agent Ricky Waters, the Flint River Farm School Preservation Society Incorporated was organized.

“I help to develop and provide the preservation society with educational resources and hands-on farm techniques and strategies. I also provide the community with farm related activities when they become available in different areas,” Waters said.

Furthermore, Waters said that educating residents about the history of the resettlement project will have a positive effect on the community.

“It will show the community how far the project dates back and display how techniques and skills have developed since its beginning,” Waters said.

Also, Whitehead said one of the major projects concerning the park is the restoration of one of the Flint River Farm’s original homes. Plans are to add the park and the home to the National Registry of Historical Places.

One of the Flint River Farm programs supported by FVSU’s Cooperative Extension Program is Heritage Day. The event is celebrated in February at the Flint River Farm Park. Terrell Hollis, meat plant manager and assistant farm manager at FVSU, conducted a meat processing demonstration on site. Other displays furnished by FVSU include the Mobile Information Technology Center and the Life on the Farm Mobile Exhibit.

During Flint River Farm Heritage Day, students in Macon County get a chance to experience how residents picked cotton, prepared meat for consumption and watched cowboys ride horses. The Flint River School Preservation Society hopes to educate youth about farming by going to the schools in Macon County and discussing the Flint River Resettlement Project.

“We have a lot of history here in Macon County based on the ties between the cities of Oglethorpe and Montezuma,’ said Jimmy Daniels Jr., mayor of Oglethorpe, Georgia.

“For them to have this event annually gives insight on how far we have come along not only as a community, but as a race in itself,” he said.

Daniels said Heritage Day is popular in Macon County and promotes diversity among the community. “You can’t spell community without unity, so we need everybody to participate, learn what’s going on to know where we come from.”

For more information about the Flint River Farms Resettlement, visit www.flintriverfarms.org.

Sources:

Cleveland Whitehead Jr.

Ricky Waters, retired Macon County Extension agent

Flint River Preservation Society

Tuskegee University