The recent outbreak of Escherichia coli (E. coli) in romaine lettuce is becoming a multistate issue, with some cases reported in Georgia. To help prevent such illnesses, an antibacterial essential oil could be the solution to inactivating foodborne pathogens like the harmful E. coli O157:H7 strain.

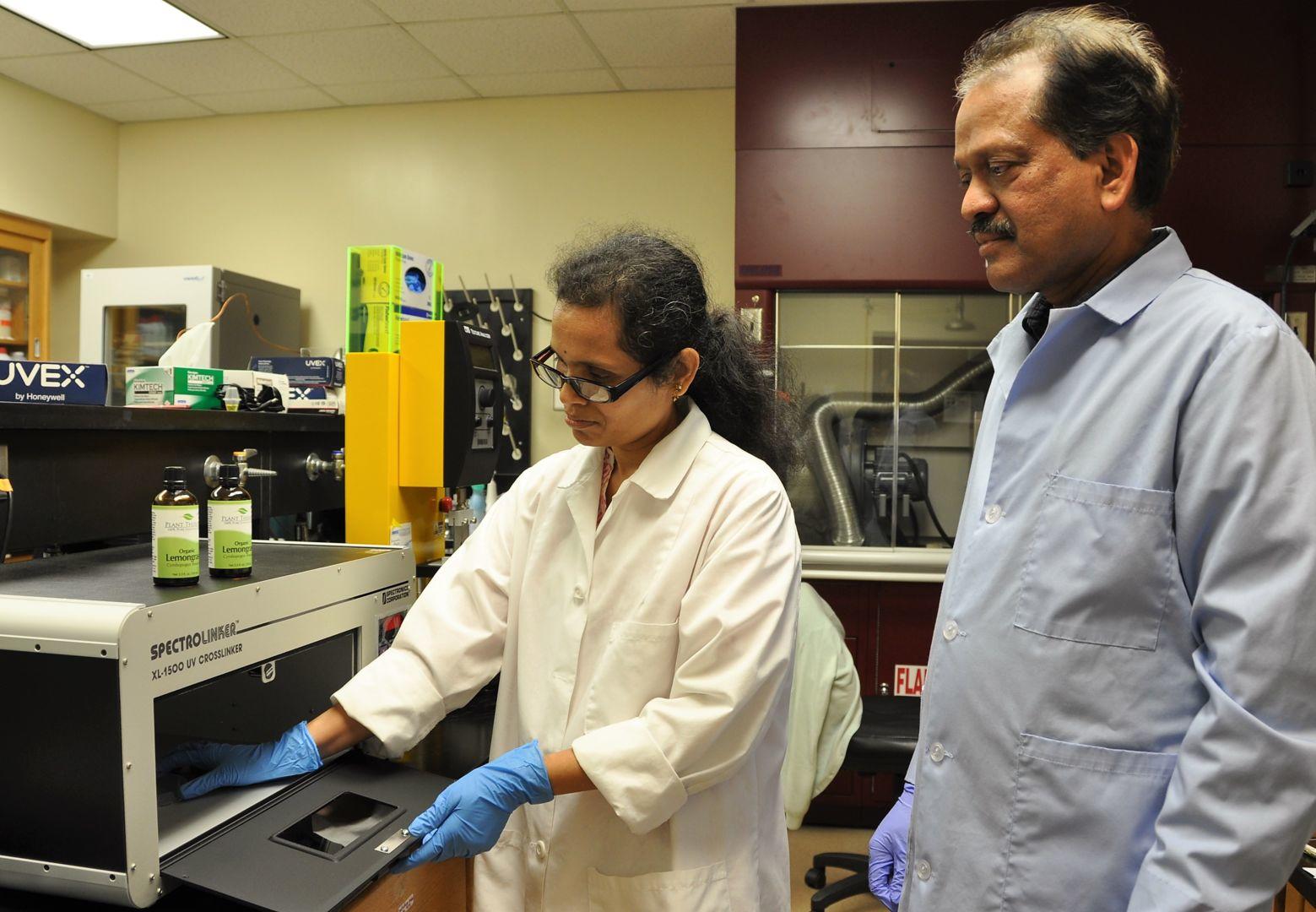

E. coli O157:H7 causes bloody diarrhea and can sometimes cause kidney failure and even death. Dr. Ajit Mahapatra, a Fort Valley State University associate professor of food and bioprocess engineering, and his graduate assistant, Hema Degala, found that this particular strain can be significantly reduced on the surface of goat meat using continuous ultraviolet-light (UV-light) and lemongrass oil.

The first to use this combination on goat meat, Mahapatra said this research could make an impact in the food industry. Widely consumed in Africa and Asia, goat meat is an important source of animal protein. Demand is rising in the U.S. because of the growing ethnic population and possibly due to the nutritional value of goat meat over the other red meats. However, E. coli O157:H7 is just as prevalent in goats as it is in cattle.

Degala, who is assisting the associate professor on this project as part of her master’s thesis, said multiple studies report that lemongrass oil reduces contamination. Familiar with using this essential oil as a cooking ingredient, she and Mahapatra decided to combine it with UV-light, which is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved technology for surface decontamination.

“Lemongrass oil or any other essential oils are good for killing bacteria. Some studies have found that lemongrass oil is the most effective,” Mahapatra said.

Because most microorganisms exist on meat surfaces, he and Degala selected different intensities of UV-light and different concentrations of lemongrass oil to determine what would be more effective. Their research shows that combining 1 percent lemongrass oil with a 200 µW/cm2 UV-light intensity for two minutes reduced the total bacterial count on goat meat by 99.9999 percent. They did not detect a single E. coli colony after treating with this combination.

Using simple, low-cost benchtop equipment, Mahapatra said meat processing plants of any size could easily adopt non-thermal alternatives like lemongrass oil and UV-light for decontaminating meat of other small ruminants such as sheep and lamb.

“Thermal processing of raw meat is not preferred due to the potential effect on the quality of the meat. It changes the color and texture,” he said. Degala added that another issue affecting the quality of the meat is chlorine-based washing techniques used by processing plants to sterilize the surface from foodborne pathogens.

“These chemical methods leave a chlorine residue in the meat that causes health concerns. We looked at alternative technologies (lemongrass oil and UV-light) that do not result in these changes,” she said.

Moreover, she and Mahapatra look forward to seeing how they can use the combination to make it suitable for commercial applications. “Generally, consumers will be readily receptive of any essential oils because most people know they have a lot of therapeutic values. Our goal is to increase the shelf life of goat meat by using technology that not only keeps it safe for the consumer, but also adds certain values,” Degala said.

Although lemongrass oil does not have any side effects, their concern is its effect on two sensory properties. The oil resulted in the goat meat changing color, and the strong odor may not be acceptable to consumers. “We may try using capsules in the packaging instead of directly applying it on meat surfaces,” Mahapatra said. “A lot of work still needs to be done. We plan to use pulsed UV-light, which takes only seconds instead of minutes to achieve the same bacterial reduction.”

Food Control, an international journal that provides essential information for those involved in food safety and process control, published the FVSU team’s work. Serving as principal investigator, Mahapatra collaborated with Drs. Govind Kannan, dean of FVSU’s College of Agriculture, Family Sciences and Technology, and Ali Demirci, professor of agricultural and biological engineering at Pennsylvania State University, on this project. “I anticipate working with more students on using UV-light and other new non-thermal technologies in the future,” Mahapatra said.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) (Evans-Allen, 1001168) and the 1890 Association of Research Directors (ARD) Food Safety Consortium supported this work.

FVSU’s Georgia Small Ruminant Research and Extension Center (GSRREC) is a national leader in goat research. For more information about food safety projects using UV-light on goat meat, contact Mahapatra at (478) 825-6809 or mahapatraa@fvsu.edu.